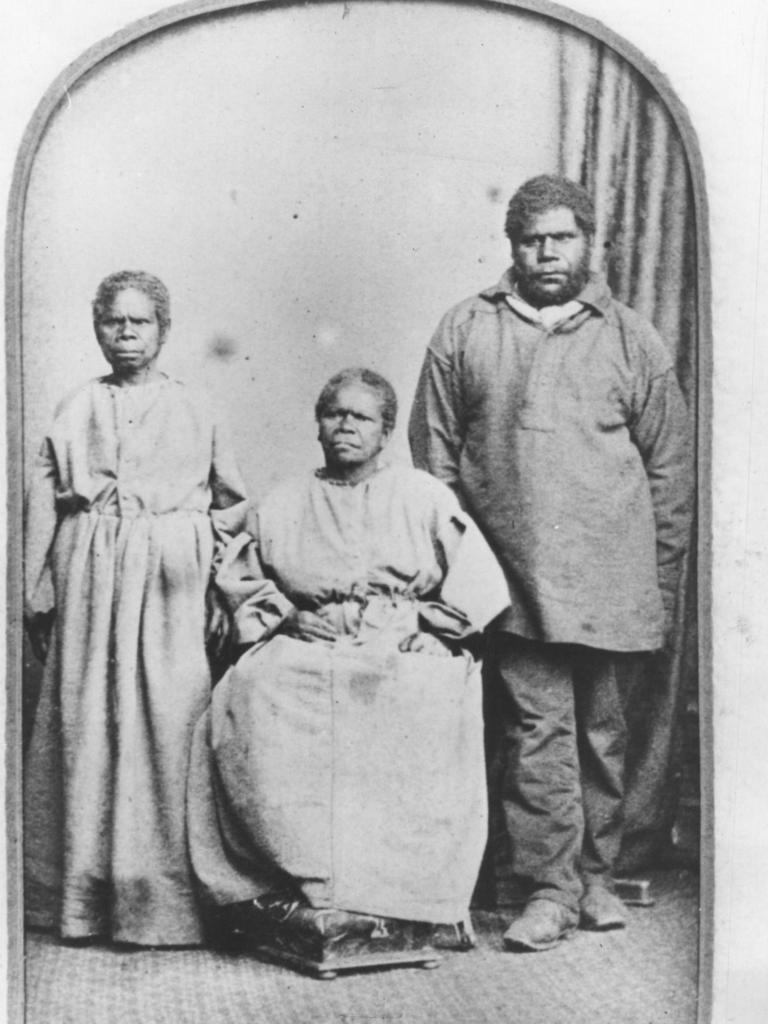

And many know William Lanne or King Billy, as he occasionally introduced himself and was often referred to by the colonial newspapers of the day.

For decades, Truganini and Lanne were regarded as the last full-blooded Tasmanian Aborigines and their deaths were said to have marked the extinction of their race.

Thankfully, most, if not all, now know this shallow and racist description of Truganini and Lanne is offensive to the contemporary Tasmanian Aboriginal community, whose families survived the British occupation and who continue to live on the island, and just plain wrong.

So, how is it that the only two historical Aborigines widely recognised by the non-Aboriginal community on the island happen to represent the extinction fable for Tasmanian Aborigines?

Why don’t we know the names of any other historical Aborigines? There were 10,000, perhaps 20,000, living on the island when the British set up camp in 1803.

Few contemporary non-Indigenous Tasmanians have heard the names Walyer, Tongerlongeter, Kickerterpoller or Manalargenna, all of whom belonged to remarkable historical figures who fiercely resisted colonisation of their island and waged a guerrilla war that was highly successful for many years, despite being vastly outnumbered by the colonists and at a serious technological disadvantage to them.

Such names and their courageous deeds have been lost in history, left as fleeting mentions scattered in the fine print and footnotes in old history books, colonial newspapers, settlers’ journals and government records.

Until now.

A new wave of research into Tasmania’s historical archives is slowly piecing together lost fragments and references to these leading Tasmanian Aborigines that have been buried in history for the best part of 200 years.

It’s painstaking detective work, cross-referencing tiny gems of information found in settlers’ journals with other sources, such as the news of the day and government records, to glean long forgotten insights into historical events.

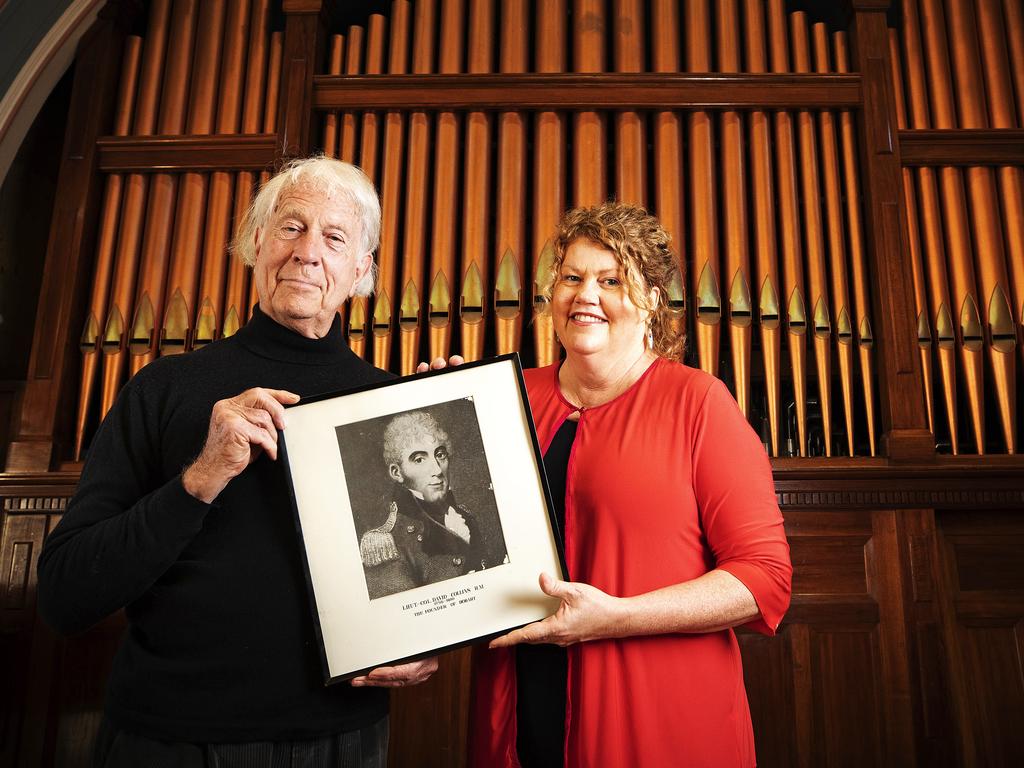

Historians such as Henry Reynolds, Robert Cox and Nicholas Clements are among those at the forefront of this new wave of research trying to exhume and reconstruct the personalities and motivations of Aboriginal Tasmanians in colonial times.

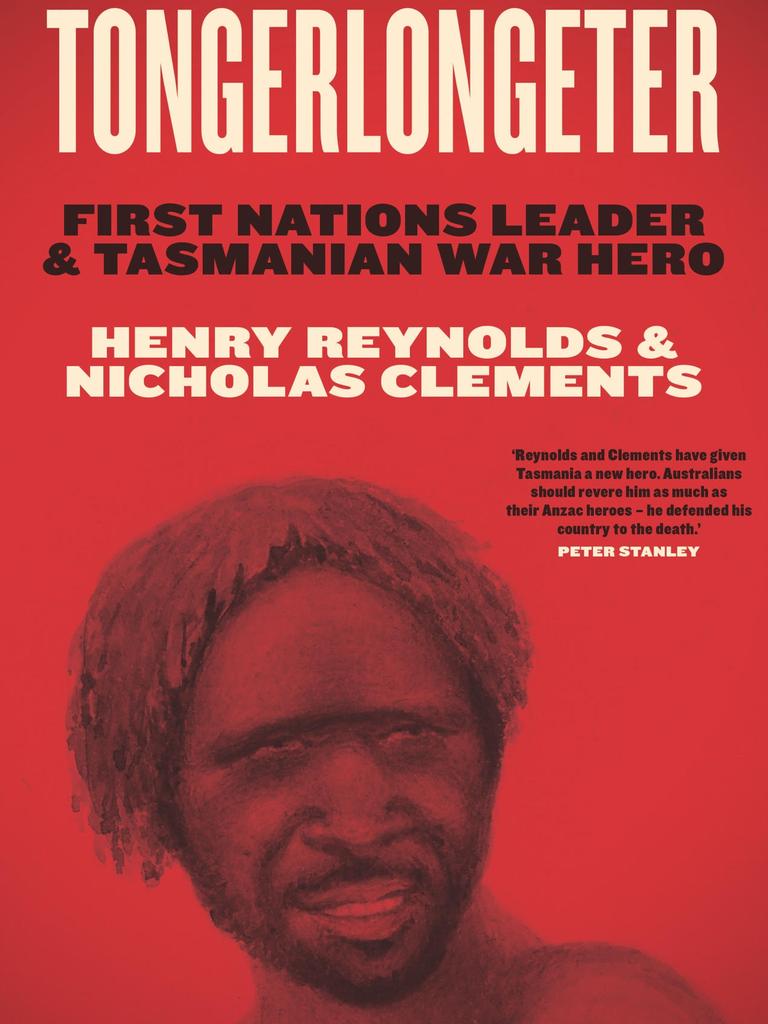

Professor Reynolds, one of Australia’s leading frontier war historians, and Dr Clements, an eighth-generation Tasmanian who teaches history, philosophy and psychology and is an adjunct researcher at the University of Tasmania, have joined forces to release the intriguing biography, Tongerlongeter: First Nations Leader and Tasmanian War Hero.

The book tells the complex story of a powerful, tall warrior and negotiator, who led his people bravely. It says Tongerlongeter was the likely military mastermind behind a veritable five-year storm of Aboriginal resistance in the late 1820s, in which the locals mounted highly strategic attacks on convicts and settlers, their huts, families, fences and sheep.

“He was the leader,” Professor Reynolds says. “He was the general.”

Leading an amalgamated posse of Aborigines from the Oyster Bay and Big River nations, which traditionally ranged from the East Coast into the Midlands and up to the Central Highlands, Tongerlongeter negotiated with neighbouring Aboriginal tribes in the North, with whom his people had longstanding grudges, to drop their grievances and unite against the colonists.

The mob he led had been disconnected from their traditional way of life; their hunting and fishing grounds, ochre deposits, stone tool quarries and sacred places overrun by settlers and convicts, who built fences, huts and paddocks, and readily defended them with firearms.

Tongerlongeter’s group adopted guerrilla war tactics and a desperate lifestyle.

Forever on the move, they set up temporary camps in safe, hidden places, where women and children could be left, while small, nimble units of men, as many as three units at a time, would conduct reconnaissance in different directions from the base camp, scouting for vulnerable colonials to raid and terrorise.

When a target such as a settlers’ hut was made, the attack unit would first hide and monitor the scene to establish who was using it, map where the exits were, and observe the settlers’ routine. Sometimes they would use decoys and diversions, such as noises or setting fire to fences, to draw settlers into the open or to intimidate them. This would often establish where any firearms were kept.

Tongerlongeter’s mob was masterful at moving with stealth through the bush, and fashioned spears, with tips as sharp and hard as nails, which they threw with deadly accuracy over long distances.

Once the signal to attack was given, the raids were often shockingly bloodthirsty. Mercy was occasionally, but rarely, shown, more often the settlers felt the full wrath of an angry mob of expert hunters who felt deeply aggrieved and were motivated by the firm belief they had right on their side.

They were fighting for their country. Professor Reynolds says colonist James Erskine Calder was among many enlightened voices on the island at the time who described the Aborigines as “patriots” and “honourable enemies”.

After the bloodshed, Tongerlongeter’s mob would return to the main camp and get back on the move or set up for the night ready to leave in the morning. They chose campsites that were strategically sound defensively and posted small outlying groups of men as lookouts for early warning of any reprisals for their attacks.

These campaigns inspired terror in the colony, and Governor George Arthur responded desperately by launching a massive military operation in 1830 — the infamous Black Line — in which more than 2000 armed settlers, soldiers and convicts marched through the Tasmanian landscape for weeks making as much noise and mayhem as they could.

The goal was to capture, kill and terrorise the Aborigines.

“This was war,” Professor Reynolds says. “The [Aborigines led by Tongerlongeter] were a serious threat to the settlers and the colony. It’s a tribute to the power of their resistance.”

Tongerlongeter was, however, more than just a warrior. He was also an accomplished negotiator who walked into Hobart with official British conciliator George Augustus Robinson to try to formulate a peace deal and met Governor Arthur at the original government house, which was sited in Macquarie St, Hobart, where Franklin Square is today.

On New Year’s Eve 1831, however, having lost his arm, his country, and all but 25 of his mob after years of warring, Tongerlongeter agreed to an armistice and left mainland Van Diemen’s Land to live as an exiled king, but without any of the usual royal treatment, at the infamous Wybalenna detention camp on Flinders Island, where his countrymen died like flies.

History is written by the victors — everybody knows this phrase, it’s a potent adage repeated many times by many voices through the ages, dating back to the mid-1700s. Variations were uttered by British wartime prime minister Winston Churchill and German Nazi war criminal Hermann Göring who, during World War II, used the (translated) version: “The victor will always be the judge, and the vanquished the accused.”

With global human history full of invasions and conquests of one cultural people over another, the phrase is a warning to all who read history that it is being written from the perspective of the rulers of the day. In 21st century parlance, history is spun.

To be fair, however, there is a vast chasm between propaganda, in which events are deceitfully distorted to benefit a tyrant and history as an ancient ethical academic practice that applies the rigour of reason, footnoting, critical peer review and other hurdles. Even the fairest historian, however, is bound by his or her own perspective, cultural bias, convention, and the governmental authority of the day.

In the context of Tasmania’s written history, there is little doubt the British colonials were the victors who adjudicated the record of events, and the Tasmanian Aborigines were the accused. At the time of the invasion, the Aborigines did not put pen to paper as their own history had been recorded in an ancient oral cultural tradition dating back millenniums.

British government documents repeatedly describe the Aborigines as savages and wretches, and little if any attempt to bridge the enormous cultural divide was made. (It is staggering to think that we can learn vastly more about the cultural practices of pre-invasion Tasmanian Aborigines from records of a couple of French scientific expeditions that spent a few months on the island, than we can from the records of the first 30 years of British occupation, despite the colonists’ meticulous practice of record-keeping on most other matters.)

However, this British bias in our history did not fully explain the problem that Professor Reynolds confronted during his journey as an academic, learning from history, and as a person, travelling Tasmania and Australia. He grew up in Hobart and was educated at Hobart High School and the University of Tasmania. As he informed himself about our past, he found an eerie silence about the colonial invasion in contemporary Australian society; in its schools, universities, media and popular culture. And in this vacuum of silence all sorts of wives’ tales thrived.

Professor Reynolds wrote of the realisation that he, and generations of Australians, had grown up with a distorted, idealised and abbreviated version of the past in his bestseller Why Weren’t We Told? (2000). Much of his career since has been spent confronting this enormous cultural blind spot by mining the vast information collected by the British colonial system and duly piecing together and telling the stories of the past.

Professor Reynolds’ question about why we weren’t told, combined with simple historical curiosity, is driving a new wave of research into long-forgotten Aborigines — to flesh out their characters, unpick their motivations, understand their deeds, and ultimately tell their stories.

Next month former Mercury subeditor Robert Cox will release his biography of Kickerterpoller, Broken Spear: The Untold Story of Black Tom Birch, the man who sparked Australia’s Bloodiest War. An amazing story of a boy taken in by a respected colonial family and treated as one of their own. He learnt to speak English and do the chores of the day. His adoptive mum, Sarah Birch, described him as a good boy.

However, disgruntled after his adoptive father died, to be replaced in the family by a man who was cruel to him, Kickerterpoller cast off his English ways to join a mob of marauding Aborigines, including infamous NSW tracker Musquito, who had also been raised with colonists. He developed a reputation through the colony for taunting and teasing his victims, calling them “white buggers”, and making it clear that he was out to extract revenge on those who had stolen his land.

“His struggle made him a seminal figure in our history and one of the most influential people in colonial Australia, yet few people have heard of him, most historians have not noticed him, and even those few scholars who have bothered to look have not seen him clearly or wholly,” Cox says. “Serious wrong has been done to Black Tom Birch and his rightful place in history. Within the greater disaster of cultural genocide, his life was a profoundly personal tragedy. A tragedy of Shakespearean proportions.”

Leading historian Professor Lyndall Ryan says Broken Spear is “the first biography ever written” about “an important Tasmanian patriot” who was greatly feared.

University of Tasmania Pro-Vice Chancellor, Aboriginal Leadership, Greg Lehman and Aboriginal researcher Patsy Cameron are writing an entry about Manalargenna for the Australian Dictionary of Biography, and flirting with the idea of writing a book about the great Tasmanian Aboriginal leader.

“Patsy and I have been talking about doing something on him for years. I’m not sure why it’s taken so long for anyone to write his story,” Professor Lehman says.

Perhaps part of the hesitancy is that Professor Lehman and others in the Tasmanian Aboriginal community are descendants of Manalargenna, who is writ large in the journals of Robinson, and the prospect of approaching such a significant ancestral subject is especially daunting. “When I first started researching Manalargenna in the 1980s, it seemed hardly anyone had heard of him,” Professor Lehman says. “That’s not the case any more, but in the wider community Tasmanians know more names from the First Nations people of America [such as Geronimo] than they do Tasmanian Aborigines.”

Professor Lehman suggests that the story of North-West Coast tribal warrior Walyer, properly fleshed out, would have important themes that resonated strongly with contemporary issues for women. Walyer was a fierce and widely feared leader, even within her own family group. Other fascinating subjects for closer investigation, he suggests, would be Walter George Arthur, who he described as the first Tasmanian Aboriginal activist and who wrote directly to the Queen complaining about Wybalenna. Arthur’s deeds helped inspire contemporary Aboriginal activists such as Jim Everett and Michael Mansell.

Author Cassandra Pybus’s Truganini: Journey through the Apocalypse, released last year, can probably be included in this new wave of historical endeavour in that it is a modern reinterpretation of a story told many times.

If we are meant to learn from history to avoid repeating the mistakes of the past, as 20th century American philosopher George Santayana advised, what use is a record of events written solely from an oppressor’s perspective? What use is a record in which we can expect the glory of a victor’s triumphs and virtues to be amplified and shame downplayed or written away?

Professor Reynolds says that a deeper, more complete understanding of history, which tried to understand the motivations of both the victors and the vanquished, taught valuable lessons of great importance to contemporary Australia. He said it was only through an understanding of the motivations and personalities of Tasmanian Aborigines, convicts, settlers, sailors, soldiers and the British authorities that the truth of history could be gleaned from the records.

The colonists fighting on the frontline were mostly convicts.

“And most of those killed were convicts. They didn’t choose to be here, they were young, urban English men with no military training,” he says. “British soldiers killed fewer than they hung. They hung 250 people in [Governor] Arthur’s time.

“A better understanding of these events reveals that the convicts and the First Nations peoples were both victims of the British Empire, and this was all very much a product of the expanding European empire.”

A deeper understanding of the historical events of colonisation, which accepts Aboriginal land was invaded and that the resulting conflict with Aborigines was full-blown war, did not necessarily have to lead to any sense of personal guilt, he says, as most of the ancestors of white Australia were dumped at gunpoint on this island, against their will, in chains.

A better understanding of free settlers revealed that many had not the faintest idea that by emigrating they were unknowingly enlisting in a frontier war where their families would be terrorised or killed unless they took up arms against the Aborigines. The Aboriginal resistance had been significantly downplayed in recruitment material for British emigrants.

Professor Reynolds says a deeper understanding of our history could, like George Santayana wisely says, help us avoid repeating the mistakes of the past, and draws parallels between the Tasmanian frontier war and the invasion of Afghanistan by Allied troops.

The American-led forces faced an inordinately complex cultural heritage in Afghanistan in which enmities between groups had been exacerbated by internal conflicts between war lords and invasions by foreign powers. These complexities were further tangled by a growing resistance across the Middle East to American imperialism at the same time as a determined push for democracy and freedom had been mounting.

A deep understanding of these political, historical, religious and cultural complexities was vital in the success of any mission by Allied forces. Such an understanding may even have warned that there was no reasonable chance of success and that military invasion would struggle to achieve anything.

“I think the fighting in Tasmania was part of a global resistance to empire,” Professor Reynolds says. “Tasmanians had been living in isolation for 300 generations, their way of life and customs were entrenched. Parts of rural Afghanistan were also very traditional societies. You can’t just sweep in and change a society and rebuild it in your own image.”●